“I think it; therefore, it must be true.“

Most people think of Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and imagine someone washing their hands, organizing things, and repeating random behaviors because of their intrusive urges. But did you know that intrusive thoughts are very normal and that 80 percent of the population has them? The question is, therefore, why do only some people develop OCD?

The metacognitive model for OCD puts little emphasis on the content of intrusive thoughts but focuses on how a person with OCD relates to them and what he believes about them. MCT for OCD aims to develop a different relationship with intrusive thoughts, so they no longer seem important nor factual.

What sets MCT for OCD apart from other treatments is the role of metacognitive beliefs about intrusions.

Metacognitive therapy for OCD – A step by step guide

A person with OCD becomes distressed by intrusions, which are thoughts, images, feelings, and urges. Intrusive thoughts may sound like, “The house is contaminated with rat poison.” Intrusive thoughts are also called obsessions.

Obsessions are normal, and most people report having them from time to time.

For example, it is normal to have images of unwanted violent or sexual acts and thoughts of crashing into another car while driving at high speed.

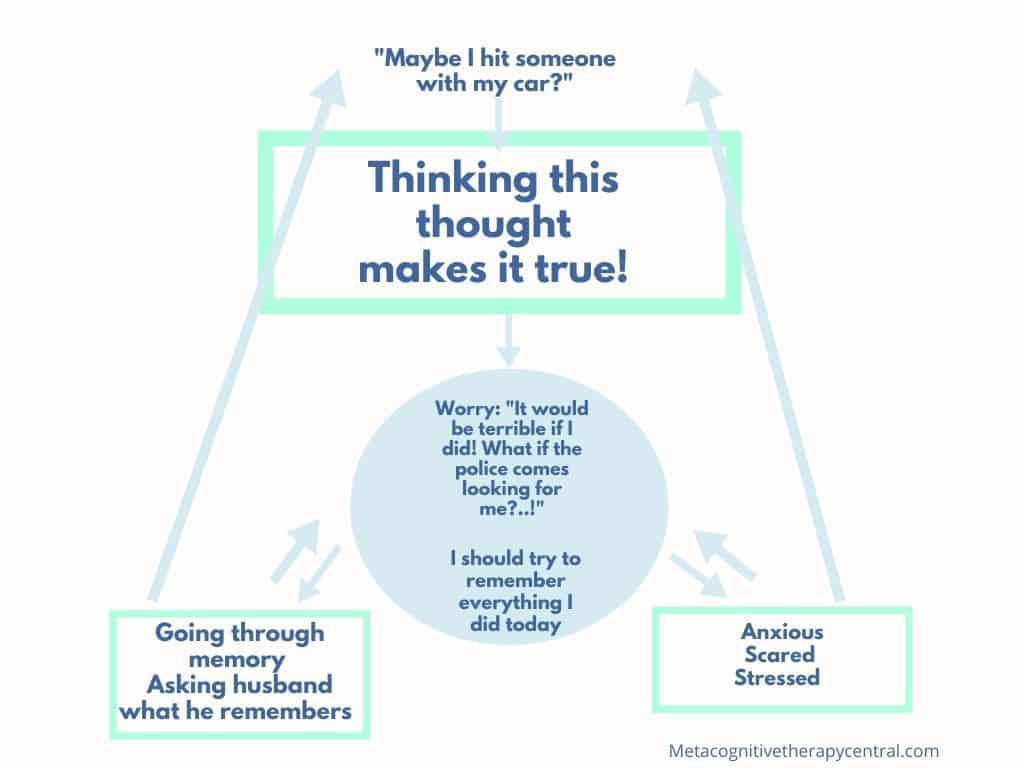

Obsessions are intrusive thoughts, images, and impulses that happen against a person’s will and are seen as repulsive and uncharacteristic of one’s identity. Obsessions often have violent, sexual, or religious content. Obsessions can also be doubts: “Maybe I hit someone with my car?“

Step 1 – The problem is not the problem

A patient with OCD must understand how the problem is not accidents, violence, or contamination but thoughts about accidents, violence, and contamination.

At the early stages of treatment, the MCT therapist will ask: “Is the problem that the house is contaminated, or is the problem your thought that it is contaminated?“

The problem for the person with OCD is not contamination, accidents, or unlocked doors. The problem is having a thought about contamination, accidents, or unlocked doors that makes the person with OCD believe in its validity.

An MCT therapist will show the patient alternative strategies for dealing with intrusions through a technique called detached mindfulness (DM). Detached mindfulness is a technique used to step back from thoughts. It is a “do nothing” to thoughts and feelings instead of neutralizing, transforming, worrying, suppressing, or ruminating about thoughts (2).

Detached mindfulness: mindfulness means being aware of thoughts, feelings, memories, and beliefs, and detachment means not engaging with thoughts, feelings, memories, and beliefs, and that a person (the self) is separated from these inner events.

Step 2 – Metacognitive beliefs make you believe that thoughts come true

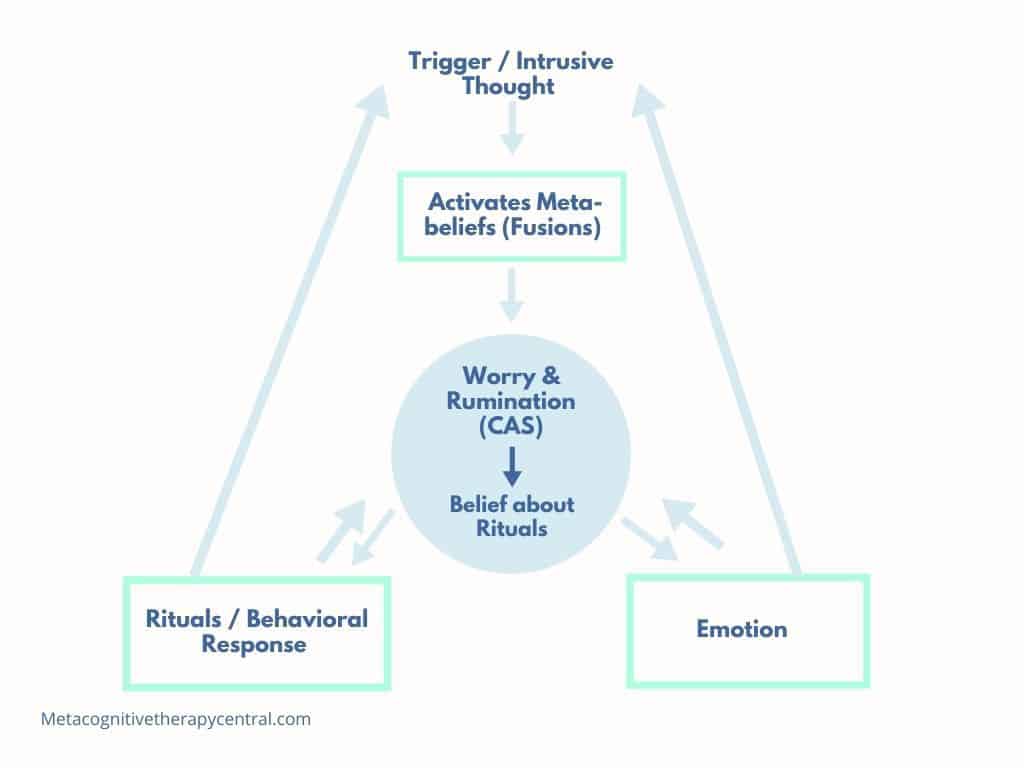

Intrusive thoughts activate a person’s metacognitive beliefs about the importance of the thought.

Metacognitive beliefs about intrusive thoughts are called fusion beliefs(5) and tell a person that intrusive thoughts are important. Fusion beliefs are divided into three areas:

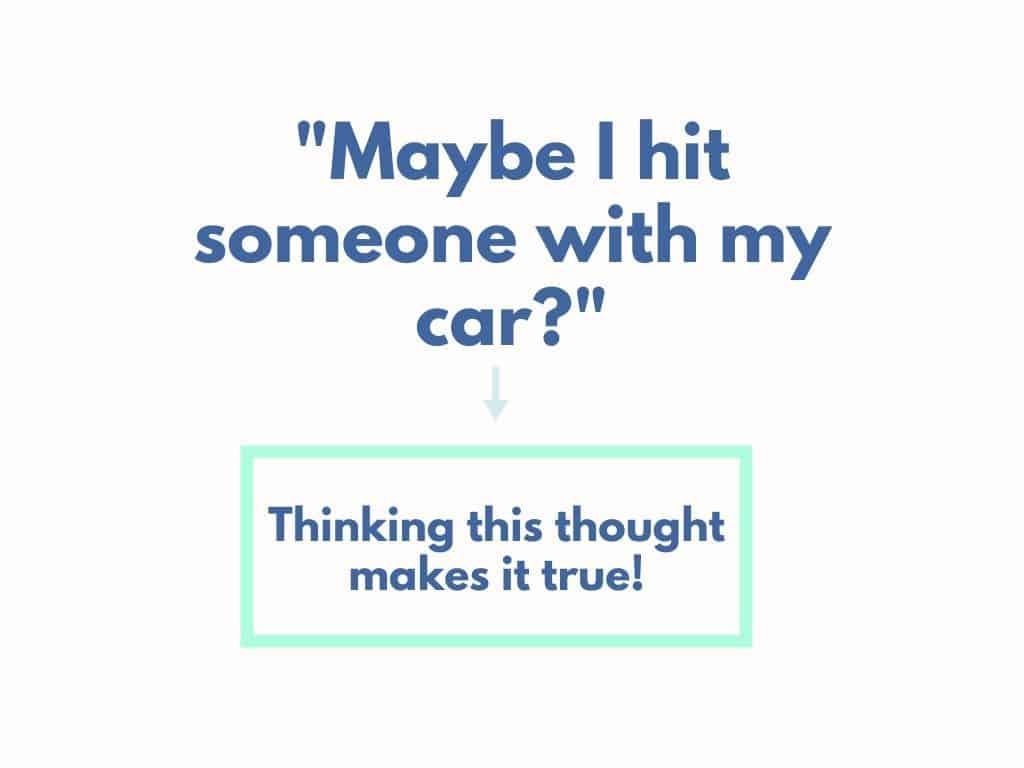

1) Thought-event fusion (TEF)

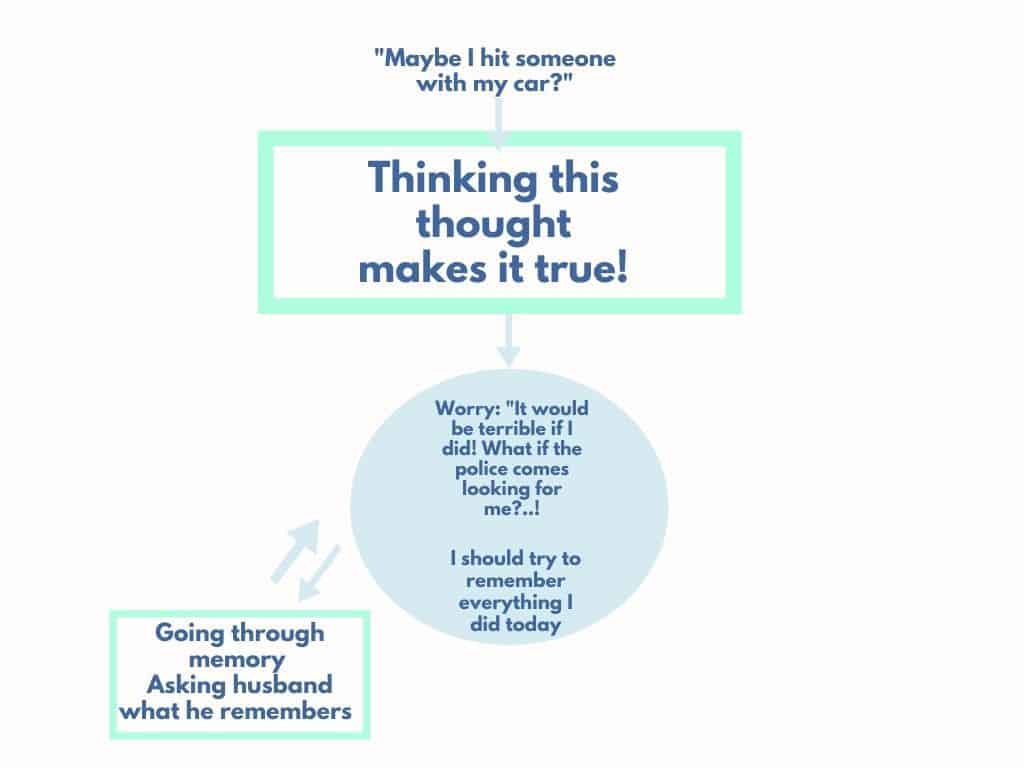

TEF is a belief that intrusive thoughts can make certain things happen. For example, if a person thinks, “Have I killed someone?” the thought itself leads to the belief that he has probably killed someone.

Examples of thought-event fusion:

“Having a thought about my house being contaminated means that it is true.”

“Having a thought about an accident means that it must have happened.”

2) Thoughts-action fusion (TAF)

TAF is the belief that intrusive thoughts, feelings, or impulses have the power to make a person do unwanted things. For example, if a person has an urge to stab someone while holding a knife, he believes that he will do it.

Another version of this belief is that having an intrusive thought while doing something (for example, having a thought about illness while walking into a room) has the power to make the thought more real.

Example of though-action fusion:

“Having a thought about strangling the baby will make me do it.”

3) Thought-object fusion (TOF)

TOF is the belief that thoughts and feelings can be transferred into things so that they can cause harm to oneself or other people.

For example, people who hoard struggle to throw something away because of a possible TOF belief.

Example of thought-object fusion:

“Having bad thoughts and feelings will ruin objects, and I will never escape from that experience.”

People with OCD usually have one or several of these fusion beliefs. However, fusion beliefs are incorrect and give intrusive thoughts excessive negative importance.

Therefore, when a person with OCD has intrusive thoughts, their metacognitive beliefs about the importance of that thought get activated. This process causes anxiety, guilt, disgust, or anger.

Because of metacognitive beliefs, intrusive thoughts are perceived as a sign of threat that needs to be avoided or neutralized. This is the reason that people with OCD do rituals.

An MCT therapist will ask: “It sounds like having that thought means something negative. What does it mean to you?” and “Is having that thought harmful or dangerous?“

Once the patient understands the connection between intrusions and fusion beliefs, the therapist challenges the fusion beliefs. This happens verbally or through experiments. For example, the therapist might ask her patient to exaggerate intrusive thoughts to see if the patient will act on them.

Step 3 – Compulsions (rituals) maintain OCD

Compulsions are repetitive behaviors like physical or mental rituals. The point of rituals is to reduce negative feelings or prevent the dreaded threat of intrusive thoughts.

Physical rituals include washing, ordering, checking, touching things, and repeating actions several times.

Mental rituals include achieving a specific state of mind, thinking “safe” thoughts, repeating words, and counting numbers. Other mental rituals include suppressing or removing unwanted thoughts.

“I have to check the stove, or my anxiety won’t go away.”

“I have to feel calm and clear; otherwise, I’ll make a mistake.”

“I must wash until I have no doubts.”

Why Rituals are Problematic

The problem with rituals is that they increase the likelihood of having more intrusive thoughts and feelings that encourage the continuation of rituals.

Performing rituals every time an intrusive thought comes up prevents people from learning that intrusions are just thoughts and that they are not important.

For example, neutralizing the thought, “What if I stab my wife?” prevents that person from realizing that thoughts don’t have the power to make him do it.

People with OCD make up their own rules for when to stop the ritual. These rules are not realistic or useful.

For example, a person with a washing ritual has the rule, “I am going to wash more this time than last time to be sure it is done well.” Unfortunately, this rule leads to increased washing which, in the end, becomes very time-consuming.

It is not uncommon for people with OCD to become depressed because their rituals become very extensive and prevent other daily activities.

The next step in therapy is, therefore, to uncover the patient’s rituals. The patient needs to understand that the rituals are unrealistic and not logical.

The therapist will challenge these rules and suggest that the patient follow more realistic rules (for example, washing hands for 30 seconds instead of ten minutes) or ban the ritual completely to check if bad things will happen as a result (becoming sick from germs).

Aside from rituals, people with OCD also use other coping behaviors in response to intrusive thoughts.

The Role of Worry and Rumination in OCD

It is also common in OCD to worry, ruminate, and analyze as a response to intrusive thoughts. Again, the aim is to avoid the threat or danger that is portrayed by intrusive thoughts.

For example, a person who has an intrusive thought, “Did I check for any remaining guests before I closed down the restaurant?” will worry about it because she believes that worrying will make her cautious and reduce the risk.

A person with the intrusion, “Maybe I hit someone with my car?” will ruminate to search her memory for any gaps or signs of an accident.

However, worry and rumination contribute to inflating the sense of threat. They also prevent people with OCD from seeing the thought as only an idea in the mind that can be let go.

Therefore, worry and rumination maintain OCD.

Worry and rumination are used by people with OCD to plan for and avoid threats. But they inflate the sense of threat and maintain OCD.

The role of threat monitoring in OCD

Monitoring for danger or threats is another coping behavior in OCD.

For example, people monitor for signs of contamination in the environment, “bad” thoughts in their mind, certain feelings, symmetry, or gaps in memory.

Just like worry and rumination, threat monitoring only inflates the sense of threat and encourages more monitoring.

Is MCT for OCD effective?

MCT is effective for treating OCD, and it can better help OCD patients who don’t respond to other therapies like Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

MCT for OCD changes how the patient thinks about his intrusive thoughts by changing his metacognitive beliefs about the importance of thoughts. Treatment is successful when the patient realizes that intrusive thoughts are simply events in the mind that don’t need to be neutralized through rituals.

MCT can very quickly help OCD patients to recover because the success lies in changed metacognitive beliefs rather than a decrease in the level of intrusive thoughts.

Intrusive thoughts will also eventually decrease because the patient no longer responds to them.

The effect of MCT for OCD

A study (7) comparing group Metacognitive therapy with group Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for OCD found that the patients who received MCT improved significantly more than the CBT group.

The results showed that patients who received MCT group therapy improved much more over the 12-week course than the CBT groups. These results were not influenced by age, how many diagnoses the patients had, symptoms of depression, or medications they took.

Another study (8) examined the short-term effect of MCT for treatment-resistant OCD. The study also measured changes in brain activity before, during, and after five MCT sessions.

The results showed that OCD symptoms decreased after receiving MCT. Furthermore, changes in brainwaves accompanied these reductions, showing that MCT creates neurobiological changes. In this case, the changes were connected to higher brain functions like cognition and memory and being alert and focused.

There are more studies on MCT’s effect on OCD. You can read about them in this post.

Do some people not recover from OCD with MCT?

Metacognitive therapy is based on changing the relationship with thoughts. To achieve that, the patient needs to practice using detached mindfulness between treatment sessions.

Unfortunately, some patients don’t practice between sessions and terminate therapy before their fusions beliefs are changed appropriately. Unchanged fusion beliefs maintain OCD because the patient continues using rituals and unhelpful coping strategies to eliminate discomfort.

Unchanged metacognitive / fusion beliefs are the biggest reason that people don’t recover fully from OCD.

References

- Photo by Annie Spratt – Unsplash

- Wells, A., (2009). Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Guilford press

- Photo by Sigmund – Unsplash

- Photo by CDC – Unsplash

- Gwilliam, P., Wells, A., & Cartwright-Hatton, S. (2004). Dose meta-cognition or responsibility predict obsessive–compulsive symptoms: a test of the metacognitive model. Clinical Psychology Psychotherapy, 11(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/CPP.402

- Photo by Melissa Jeanty – Unsplash

- Papageorgiou C, Carlile K, Thorgaard S, Waring H, Haslam J, Horne L, Wells A. Group Cognitive-Behavior Therapy or Group Metacognitive Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? Benchmarking and Comparative Effectiveness in a Routine Clinical Service. Front Psychol. 2018 Dec 10;9:2551. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02551.

- Winter L, Alam M, Heissler HE, Saryyeva A, Milakara D, Jin X, Heitland I, Schwabe K, Krauss JK, Kahl KG. Neurobiological Mechanisms of Metacognitive Therapy – An Experimental Paradigm. Front Psychol. 2019 Apr 4;10:660. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00660. PMID: 31019477; PMCID: PMC6458268.

- Photo by Sarah Killian – Unsplash

- Photo by Towfiqu Barbhuiya – Unsplash