A research study asked children to remember specific words on a test and depending on metacognition, the kids responded differently. Older kids studied for a bit, said they were ready, and usually nailed it by recalling everything perfectly. But the younger kids studied for a bit, said they were ready and often didn’t recall the items perfectly (2).

This research highlighted that younger children may have limited metacognitive skills compared to older children and adults. Younger children don’t pay much attention to how well they remember things or understand information, compared to older children and adults, who have more developed metacognition.

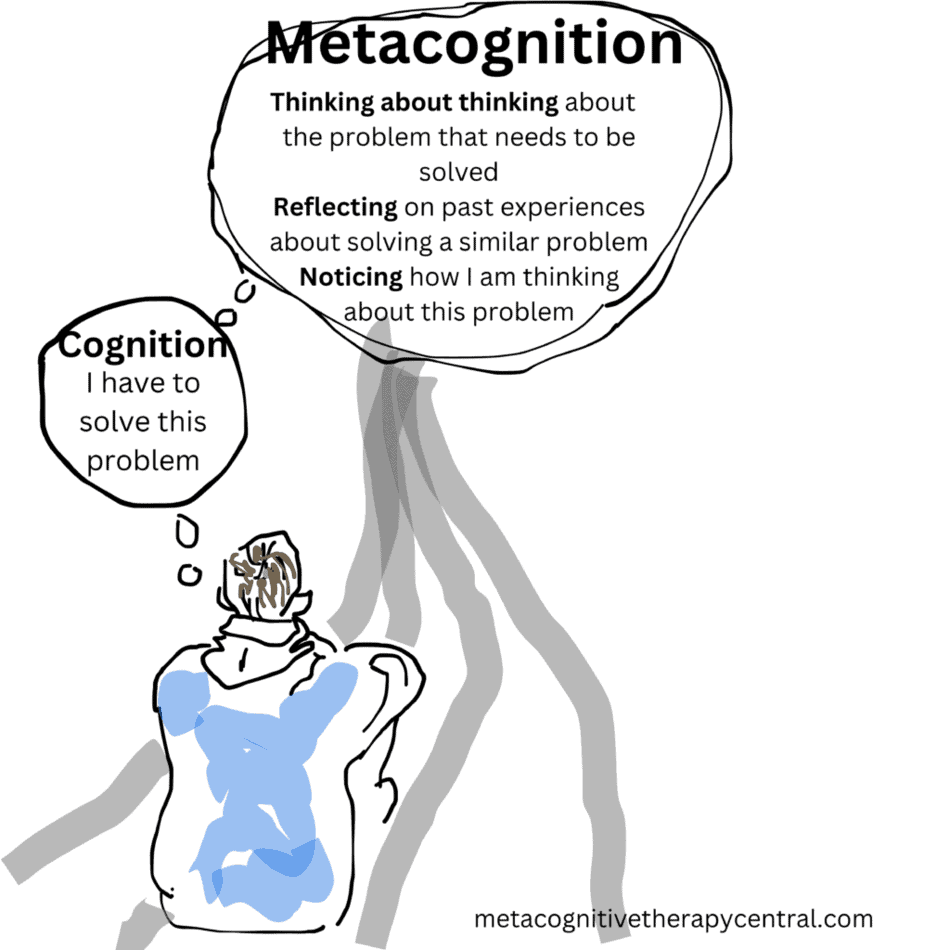

Metacognition means awareness of our own thoughts, monitoring and controlling our thinking processes, assessing how well we understand things, and employing effective strategies for learning and problem-solving. As we grow and gain more experience, our metacognitive abilities typically improve.

Metacognition has a profound impact on our mental health, learning, and growth. Metacognition is crucial in achieving mental control and help us achieve cognitive goals. So how exactly does metacognition affect us, is it purely genetic, and can we improve it to achieve important goals?

Metacognition is the ability to think about your own thinking. Metacognition is all about understanding and controlling our thinking

How does metacognition impact us?

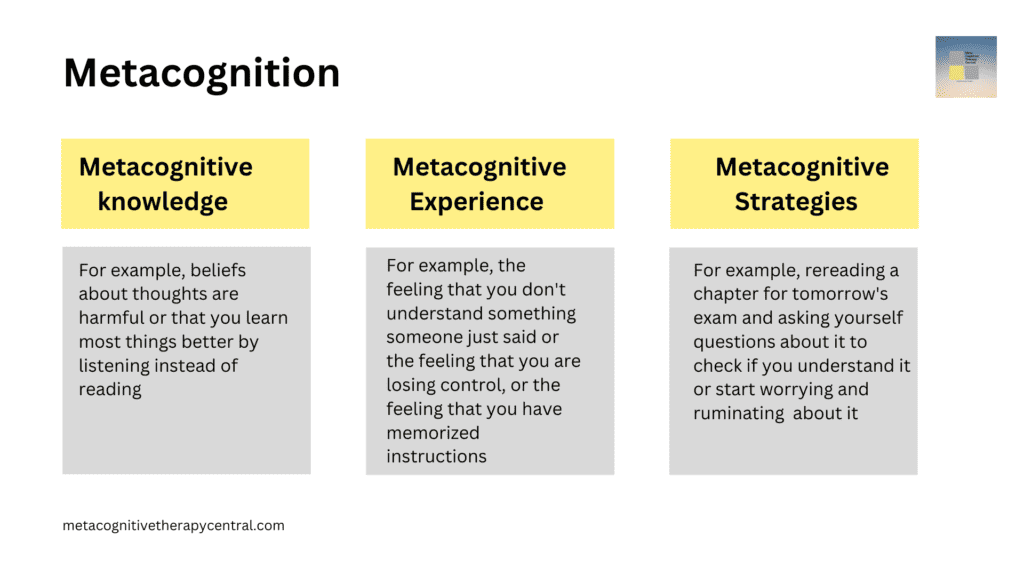

The following examples demonstrate how metacognition (consisting of metacognitive knowledge, experience, and strategies) contributes to learn and self-regulate effectively:

Metacognition’s role in learning

| Metacognitive processes | What does it do? |

| Understanding our thinking | focuses on understanding how our brains work and how we think |

| Monitoring our learning | being aware of our understanding, recognizing when we need to study more, and monitoring our progress. |

| Using strategies | knowing which strategies to use and actually using the strategies to enhance learning |

| Reflecting on our progress | looking back at our learning journey and assessing how we have grown and improved |

| Taking control of our learning | understanding how to take control and make decisions about our learning process |

Metacognition helps us understand our thinking

Understanding our thinking is like figuring out the tricks and patterns our brain uses. It means being aware of how our brain works and how our thoughts, feelings, and beliefs affect the way we learn and make choices.

An example of this is recognizing that you tend to get distracted easily while studying and that it affects your focus and learning. This, in turn, allows you to take steps to minimize distractions and create a better learning environment (like getting off Facebook and Tic Tok or going to a quiet place to study).

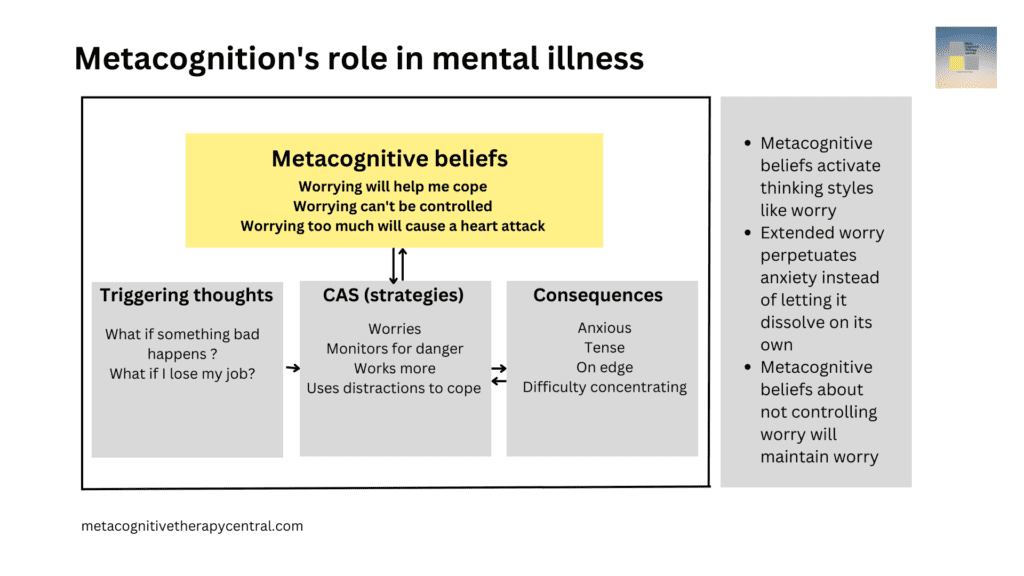

Through metacognition, we know our strengths and weaknesses in thinking and learning. And we can learn how to use our brains better and avoid common mistakes or biases. However, we may have inaccurate ideas of how our thinking works. For example, we may think that worrying about a problem will help us solve it. This is, according to Adrian Wells, the founder of Metacognitive therapy, called a metacognitive belief, and it can lead to hours of unnecessary worry.

We may also incorrectly think that we can’t control worry or that worrying can harm us mentally. According to Wells, incorrect metacognitive beliefs impact mental health negatively and are the underlying factors behind mental illness (3)(4).

Metacognition monitors our learning

With metacognition, we can figure out the best ways to learn and solve problems by monitoring our progress.

For example, when you read this post, your brain uses metacognition to understand the text. It might use strategies like pausing to check if you understand what you just read, re-reading a confusing sentence, or making connections to your own experiences. Metacognition helps you monitor your understanding and make adjustments to help you understand better.

Another example of where metacognition is involved is when studying for exams. Here, you typically use metacognitive monitoring strategies like self-testing, summarizing information in your own words, and reviewing previous mistakes to enhance understanding and retention. Metacognition helps you identify what you know well and what you still need to review, allowing you to focus your efforts effectively.

Picture your brain as a detective trying to solve a mystery. The mystery is a difficult question or problem. Metacognition is like having clues and investigative skills that guide your detective brain to find the answers and solve the mystery.

Metacognition helps us use strategies

Metacognition can help us use strategies for problem-solving, managing time, improving how we communicate with others, understanding and managing our emotions, learning from mistakes, and setting personal goals.

Basically, when faced with a complex problem or decision in daily life, metacognition can help you approach it more effectively. You may use strategies like breaking the problem into smaller parts, considering different perspectives, brainstorming possible solutions, and reflecting on the outcomes of your choices.

Let’s imagine that your goal is to learn about metacognition, so you do a Google search and decide to click on this particular post. The post looks long there is a lot of text, so with the help of your metacognition, you decide to scroll through and read the headlines first, look at the pictures, and read the colorful boxes.

Now that you have an overview, you start reading the text from the beginning, and along the way reflect on what you read, and try to relate what you read to your own experience. You might even imagine how you are teaching someone else the things that you just read. You also know from past experience, that only reading one or few sentences will not help you understand the topic well enough to teach it to someone else. All these strategies are activated by your metacognitions.

Another way metacognition guides our choice of strategy is when it comes to our emotional health. For example, metacognition guides us to use thinking strategies like rumination to figure out why we are feeling sad and hopeless (which, by the way, is not a good strategy because excessive rumination causes depression in the first place). The strategies that are guided by our metacognitive beliefs may not always be the most helpful.

Metacognition is like having a brain toolbox. It helps you understand how you think and learn. With metacognition, you can discover the best strategies for understanding and learning something, remembering things, and solving problems. It’s like having a secret weapon to become a super learner and achieve your goals.

Metacognition’s role in mental disorders

According to Professor Adrian Wells, the founder of Metacognitive therapy (MCT), metacognitive beliefs are specific attitudes people may have about their thoughts, emotions, and cognitive processes. Wells describes five types of metacognitive beliefs, that are the drivers of mental illness like anxiety, depression, and OCD (4) (16):

| Type of Metacognitive Belief | Description | How it relates to mental illness |

| Positive Beliefs about worry and rumination | Worrying/ruminating is helpful to cope with problems or prevent negative outcomes (worrying helps me cope. Rumination will help me find solutions) | Positive metacognitive beliefs activate rumination and worry initially and play a role in relapse into mental illness |

| Negative Beliefs about Uncontrollability and Danger | Thoughts and emotions are uncontrollable and dangerous, leading to feelings of vulnerability (I can’t stop worrying/ruminating. Worrying will make me go crazy) | Negative metacognitive beliefs (especially beliefs about uncontrollability) are always present in people who suffer from mental disorder |

| Need to Control Thoughts | It is important to control thoughts and suppress certain thoughts to avoid negative consequences (If I could not control my thoughts, I would not be able to function) | Negative metacognitive beliefs (especially beliefs about uncontrollability) are always present in people who suffer from a mental disorder (because they prevent people from stopping rumination and worry) |

| Cognitive Confidence | Having little confidence in one’s memory for remembering names, places, events, etc (I do not trust my memory) | This belief seems to be linked to people with OCD. The lower cognitive confidence, the higher checking behavior, and OCD symptoms |

| Cognitive Self-consciousness | The tendency to self-focused attention and monitoring of thoughts (I am constantly aware of my thinking) | This type of belief has a strong connection to rumination |

When we engage in excessive rumination and overthinking, our attention becomes overly focused on our thoughts and emotions. This constant analysis and dwelling on our inner experiences can create a heightened sense of self-awareness, leading to a hyper-focus on negative aspects or potential problems. For example, according to MCT, excessive negative self-awareness can lead to social anxiety (9).

As a result of excessive self-awareness our stress levels can increase, and we may experience heightened anxiety and emotional distress.

Additionally, overthinking can prevent us from fully engaging in the present moment and taking effective action. It keeps us stuck in a loop of analyzing and reanalyzing our thoughts without finding productive solutions. Research supports this by showing that thinking too much about solutions decreases your chances of taking action (6). This can perpetuate a cycle of negative thoughts and emotions, making it difficult to break free from distressing patterns.

Metacognitive beliefs are the thoughts and beliefs we have about our own thinking processes. They influence how we perceive and interpret our thoughts and emotions and they play a crucial role in shaping our mental well-being.

Is Overthinking Metacognition?

Overthinking, also called rumination and worry, is often mistaken for metacognition due to their reflective nature, but they are not the same. Metacognition seems to be located in a different system in the brain than cognition, where overthinking happens (4).

Overthinking involves getting stuck in a loop of repetitive thoughts, especially negative ones. Metacognition, on the other hand, is about having an overall awareness of our thought processes (monitoring our thinking) and controlling it (through metacognitive strategies). Overthinking is activated by metacognition, but overthinking and metacognition are not the same thing.

Overthinking: “I haven’t studied enough for the exam tomorrow. What if I fail?”

Metacognition: Worrying about the exam tomorrow is helpful for being prepared.

Is metacognition good or bad?

Although metacognition is a helpful cognitive ability, it can have downsides.

Metacognition is like having a personal “mind manager” inside our heads. It helps us keep track of how our brain is working and lets us control our thinking. However, just like any manager, our mind manager can sometimes make mistakes. These mistakes are what we call metacognitive biases.

Imagine your mind manager telling you that you know everything about a subject when you actually don’t. Or it might make you doubt your abilities, even though you’re actually quite good at something. These are the systematic errors or distortions that can happen when our mind manager is not completely accurate.

There are several examples of this:

Older people with diabetes often use their metacognition to understand what their doctors say about managing their blood sugar levels. However, some may wrongly assume they remember everything because they are overly confident in their ability to recall the information.

Alex is studying for a history exam and believes that he won’t be able to remember important dates and events. Due to this negative bias, he doesn’t invest enough time in studying and ends up performing poorly on the exam, reinforcing his belief that his memory is not good enough.

Another example is Sarah recounting a childhood memory at a family gathering. She recalls an event with vivid details, convinced that her memory is accurate. However, her siblings remember the event differently and provide evidence that some of the details she mentioned are incorrect.

Excessive worry and overthinking also stem from biased metacognitive beliefs and can result in heightened stress, emotional distress, and a cycle of negative thoughts and emotions.

Metacognitive biases are related to cognitive processes involving underestimating or overestimating one’s cognitive abilities, memory, and decision-making

I am absolutely convinced that there is, overall, far too little rather than enough or too much cognitive monitoring in this world.

Flavell, 1979

Is metacognition genetic?

Metacognition is a natural cognitive ability found in varying degrees within the human population (and in some animals (13)). While it’s challenging to measure its exact prevalence, it’s considered a fundamental ability that improves during adolescence and stabilizes in adulthood (12).

It seems that metacognitive ability plays a role in improved learning, enabling adolescents to focus more efficiently on what they still need to learn at a stage where learning plays a key role in developing a self-identity, self-awareness, and in their interaction with others.

However, some studies even show that three-year-old children also show metacognitive ability(11), but this ability continues to develop into adulthood.

Genetic factors of metacognition

The role of genetics in metacognition is an ongoing area of research. While specific genes associated with metacognitive abilities have not been identified, studies suggest that genetics, combined with environmental factors, contribute to individual differences in cognitive processes, including metacognition (14).

According to some scientists, metacognition in humans is shaped by a specific kind of social learning (also called cultural learning) (10) For example, the ability to interpret and predict other people’s behavior is related to the way mothers talk to their children, and how parents refer to their children’s confidence in their language during collective tasks (“Do you think you can do that?”, “Are you sure?”, “You’ve got it!”).

Metacognition is learned socially

Studies done with schoolchildren also show that the way teachers instruct pupils on setting goals, self-questioning, and interpreting how well they understand something improves their text-based and mathematical learning. This is because it improves metacognitive sensitivity (11).

Metacognitive beliefs develop from childhood experiences

When it comes to dysfunctional metacognitive beliefs that drive rumination and worry, it seems that early negative experiences, and emotional abuse in particular, play a role (8). In their research, Wells and Meyers suggest that children who experience abuse may develop positive metacognitive beliefs about the use of worry and threat monitoring to avert danger and distress. And that repeated experiences of worry can then lead to negative metacognitive beliefs that worrying can’t be controlled.

Think about a time when you realized that taking short breaks during a task helped you maintain focus and productivity. This awareness of your attention span and strategies for optimizing it reflects metacognitive abilities.

The Brain Regions Involved in Metacognition

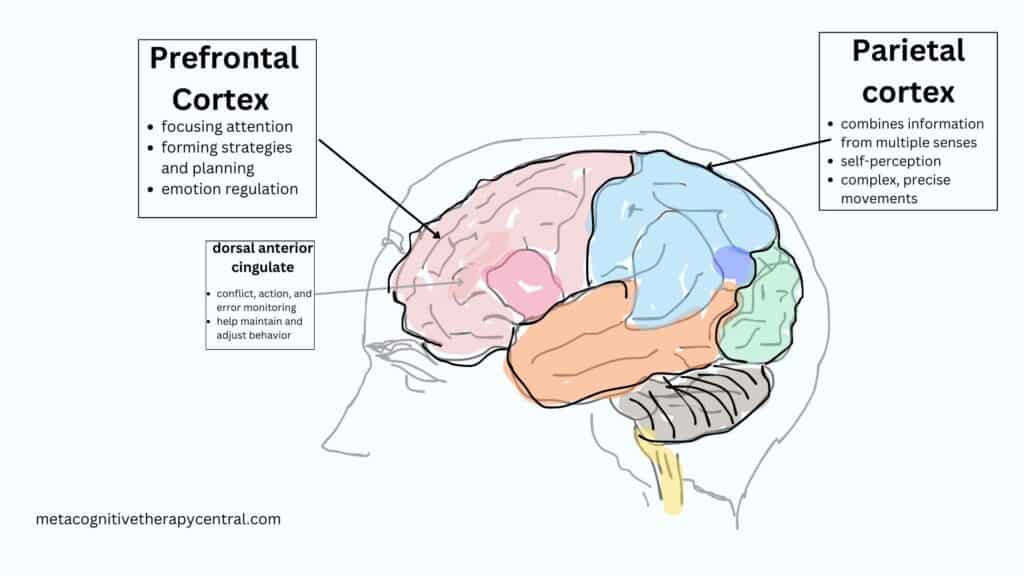

Metacognitive processes involve complex interactions among different brain regions. According to neuroimaging data (4) (15), the brain regions involved in metacognition are the pre-frontal cortex, the dorsal anterior cingulate, and the parietal cortices (see illustration below):

Can metacognition be trained?

When it comes to learning, metacognition can be trained. Some suggest, that instead of teaching children what to learn (the topics and their content), they should learn how to learn and thereby improve their metacognitive abilities for learning. One way to do this is to teach them to monitor and understand how they learn because this ability can then be applied generally across learning situations.

In the case of mental illness, metacognition can be trained in different ways:

- raising metacognitive awareness by noticing what kind of thinking you are doing: ruminating in circles, worrying yourself anxious, daydreaming about pleasant things, or reflecting?

- strengthen control over thinking (learning that you can stop rumination and worry so that you don’t get anxious and depressed)

- Increase attention flexibility (that you can control what you pay attention to, which is helpful in both educational settings, and if you suffer from social anxiety, depression, and other mental illnesses).

One way to achieve the above is through the attention training technique. To learn how to reduce rumination and worry, go to this post.

Sign up here.

References

- Photo: Dan Cristian Padure

- Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906-911.

- Hjemdal, O., Stiles, T., & Wells, A. (2013). Automatic thoughts and meta‐cognition as predictors of depressive or anxious symptoms: A prospective study of two trajectories. Scandinavian journal of psychology, 54(2), 59-65

- Wells A (2019) Breaking the Cybernetic Code: Understanding and Treating the Human Metacognitive Control System to Enhance Mental Health. Front. Psychol. 10:2621. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02621

- Photo: Adam Winger

- Papageorgiou, C., & Wells, A. (Eds.). (2004). Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment. John Wiley & Sons.

- Photo: Priscilla Du Preez

- Myers, S. G., & Wells, A., (2015) Early trauma, negative affect, and anxious attachment: the role of metacognition, Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 28:6, 634-649, DOI: 10.1080/10615806.2015.1009832

- Nordahl, H., & Wells, A. (2018). Metacognitive Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder: An A–B Replication Series Across Social Anxiety Subtypes. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 286491. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00540

- Cecilia Heyes, Dan Bang, Nicholas Shea, Christopher D. Frith, Stephen M. Fleming, Knowing Ourselves Together: The Cultural Origins of Metacognition, Trends in Cognitive Sciences,Volume 24, Issue 5, 2020.

- Schraw, G., & Moshman, D. (1995). Metacognitive Theories. Educational Psychology Review. 7. 351-371. 10.1007/BF02212307.

- Weil LG, Fleming SM, Dumontheil I, Kilford EJ, Weil RS, Rees G, Dolan RJ, Blakemore SJ. The development of metacognitive ability in adolescence. Conscious Cogn. 2013 Mar;22(1):264-71. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2013.01.004. Epub 2013 Jan 30. PMID: 23376348; PMCID: PMC3719211.

- Metcalfe, J. (2008). Evolution of metacognition. In J. Dunlosky & R. A. Bjork (Eds.), Handbook of metamemory and memory (pp. 29–46). Psychology Press.

- Polderman, T. J. C., Benyamin, B., de Leeuw, C. A., Sullivan, P. F., van Bochoven, A., Visscher, P. M., & Posthuma, D. (2015). Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nature Genetics, 47(7), 702-709.

- Qiu, L., Su, J., Ni, Y., Bai, Y., Zhang, X., Li, X., et al. (2018). The neural system of metacognition accompanying decision-making in the prefrontal cortex. PLoS Biol. 16:e.2004037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004037

- Frederick Anyan, Henrik Nordahl & Odin Hjemdal (2023) The network structure of dysfunctional metacognitions, CAS strategies, and symptoms, Cogent Psychology, 10:1, DOI: 10.1080/23311908.2023.2205258